David Stark and Lisa Goodson, IRIS, University of Birmingham

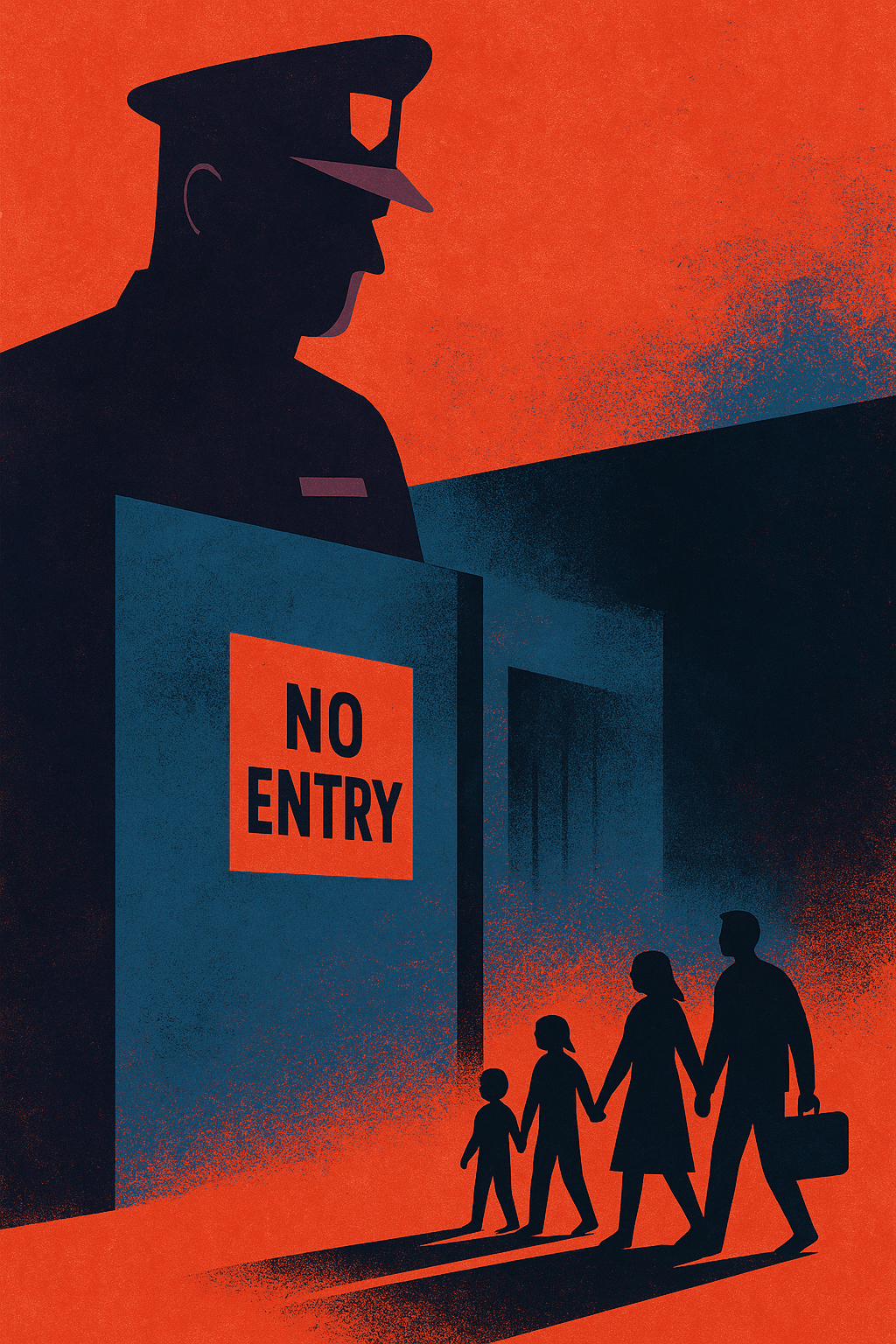

A policy turning inwards

At the Institute for Research into International Migration and Superdiversity (IRIS), we examine migration and superdiversity through empirical research grounded in lived experience. We do this from Birmingham, one of the UK’s most ethnically diverse cities and a place where migration is a lived and everyday reality. This makes it especially concerning that the government’s new White Paper, Restoring Control Over the Immigration System (Home Office, 2025), not only recycles divisive language but proposes policy changes that threaten to undermine social cohesion, destabilise essential public services, and intensify precarity for migrants already settled in the UK.

Although presented as a “clean break with the past”, many of the proposals echo longstanding punitive policies associated with the ‘hostile environment’, an approach that has consistently failed to deliver fair or functional migration governance. While IRIS supports informed debate on immigration reform, this White Paper lacks an evidence base, adopts reductive framings, and risks significant harm. Drawing on years of multidisciplinary research into migration, citizenship, welfare access, and integration, we offer this response to support a more constructive, evidence-led conversation. It is from this perspective that we express serious concerns about the tone, framing, and direction of the White Paper recently published in May 2025.

Framing migration as a crisis, not a contribution

The White Paper opens with the claim that previous immigration regimes amounted to a “squalid chapter” in UK history. The Prime Minister describes a failed “open borders experiment” that has supposedly overwhelmed public services and weakened national cohesion. This narrative is at odds with the policy record of the last two decades, which has seen increasingly restrictive immigration measures—including the points-based system, tightened family reunification criteria, and the expansion of hostile environment practices.

Assertions that migration has damaged public services overlook more immediate drivers. From 2010 to 2020, Birmingham City Council’s spending power fell by over 36% (IFS, 2023), a direct result of austerity. In 2023 Birmingham City Council issued a Section 114 notice, effectively declaring it could no longer balance its budget due to these severe financial constraints. Blaming migrants for such systemic issues obscures the structural causes of underinvestment.

In fact, migrants are essential to many sectors. In adult social care, for instance, they comprise over 17% of the workforce in England (Skills for Care, 2023). By framing migration as the problem, the White Paper diverts attention from the broader political and economic decisions that have strained public infrastructure.

Integration denied: conditional belonging and the reinvention of ‘deservingness’

While the White Paper presents integration as a key objective, its policy proposals risk undermining that very goal. A key example is the extension of the qualifying period for migrants to apply for settlement or citizenship, delaying access to rights, stability, and social participation. Rather than fostering integration, this measure prolongs insecurity, especially for children and families affected by the No Recourse to Public Funds (NRPF) condition.

NRPF prevents many migrants with temporary or limited leave from accessing welfare support, irrespective of their employment record or time spent in the UK. Extensive research has shown that NRPF intensifies poverty, homelessness, and food insecurity, particularly for children (Jolly et al., 2022; Children’s Society, 2020). IRIS’s own research highlights how this exclusionary framework pushes families into exploitative labour and poor-quality housing, undermining both individual wellbeing and social cohesion (Phillimore, 2021; Hourani et al. 2021; Jolly and Gupta, 2024).

Despite widespread calls for reform, the White Paper does not address NRPF. Instead, it reinforces a narrow vision of integration, framed around individual economic self-sufficiency. This framing overlooks how immigration policy itself creates barriers to contribution, through insecure status, restricted rights, and uneven access to work. This contradiction is further exposed by the proposal to fast-track settlement for individuals considered to have made “significant contributions,” primarily measured through high-skilled or high-wage employment. In contrast, vital forms of labour such as caregiving, community involvement, and parenting, often undertaken by women and single parents, are excluded, despite their essential role in sustaining society and promoting cohesion.

By defining value through market-based metrics, the White Paper reasserts a rigid deserving/undeserving divide (Hall, 1978; Anderson, 2013). Many workers in sectors such as care, hospitality, construction, and agriculture (vital to the UK economy) are effectively written out of the path to secure status. This approach obscures structural inequalities in access to education, employment, and legal protection, which shape who can meet these so-called ‘earned’ thresholds.

The claim that settlement and citizenship are, and always have been privileges to be ‘earned’ also distorts historical and legal precedent. Until the end of the Brexit transition period in December 2020, EU nationals had the legal right to settle in the UK under freedom of movement (see Sigona 2025). The UK’s long-standing tradition of birthright citizenship, though now curtailed, was once a defining feature of its legal landscape. Recasting rights as privileges erodes the foundations of inclusive citizenship and reframes integration as a conditional, exclusive process rather than a two-way process (Phillimore 2021).

Valuing care in rhetoric, undermining carers in practice

Perhaps the most striking contradiction lies in the treatment of migrant care workers. During the COVID-19 pandemic, these workers were lauded as essential. Yet, the White Paper now labels them as “lower-skilled” and partly responsible for suppressing wages and opportunities for domestic workers. Rather than improving pay and working conditions in the social care sector, a critical need identified by the Migration Advisory Committee (2022), the government proposes to scrap the social care visa route entirely. This is despite a projected shortfall of 500,000 care workers by 2035 (Skills for Care, 2023). The suggestion that people currently classified as unfit for work due to disability or chronic illness will fill this gap raises serious ethical and practical questions. Disability rights organisations have already raised concerns that this approach risks coercive activation of vulnerable people in the name of reducing welfare costs (Inclusion London, 2024). The removal of migrant care workers from the current workforce seriously risks deepening the existing crisis in social care, leading to severe staff shortages, subsequent rising care costs – simply an unmet demand that cannot be addressed nationally within the proposed timeframe. Such a policy also raises concerns about how the UK values those who have contributed significantly to essential frontline health services, often under precarious conditions

Neglecting common-sense reforms to asylum and labour

Although asylum is not the main focus of the White Paper, its treatment is instructive. The costs of accommodating asylum seekers in hotels, sites of anti-migrant tension and violence in 2024 (Refugee Action, 2023; The Guardian, 2024 a and b) are described as “unacceptably high,” yet the document offers no exploration of alternatives. There is no consideration of one of the most widely supported policy recommendations from civil society: lifting the ban on asylum seekers’ right to work while awaiting decisions (Lift the Ban Coalition, 2021). The absence of this proposal, or any engagement with it, speaks volumes about this White Paper’s priorities.

Allowing asylum seekers to work would: reduce dependency on state support; reduce asylum support / expenditure on hotel accommodation; address labour shortages in key sectors like social care; place asylum seekers on a pathway to ‘earned’ settlement. In a report by Lift the Ban Coalition (2021) it is estimated the policy could generate £333 million per year in tax revenues and savings.The Commission on the Integration of Refugees (2024) has similarly made clear that facilitating access to employment and language support not only aids social integration but also delivers significant economic benefits. Their recent report (Commission on the Integration of Refugees, 2024) presented economic modelling by the LSE showing that allowing asylum seekers to work after six months and providing ESOL from day one would yield a net boost of around £1.2 billion to the UK economy within five years. This figure accounts for increased income tax and national insurance contributions, reductions in asylum support payments, and multiplier effects of greater economic activity. Enabling asylum seekers to work earlier would also allow people to maintain dignity and rebuild their lives—core components of a functioning asylum system. Yet this practical employment reform is not considered. Instead, the asylum section appears under a heading titled “Tackling Abuse,” casting claimants as threats rather than rights-holders. This framing erodes public understanding of international protection obligations and entrenches harmful stereotypes.

Policy by exception: selective inclusion and strategic exclusion

Across its sections, the White Paper outlines a policy regime based not on inclusive rights but on conditional recognition. Citizenship, settlement, and access to basic services are to be selectively granted to those deemed economically valuable, socially compliant, and politically uncontroversial. Others, including those seeking sanctuary, doing essential but undervalued work, or raising families on modest incomes, are treated as peripheral. This selective inclusion threatens the very goals the government claims to uphold: integration, fairness, and social cohesion. It signals that no matter the effort or contribution, some groups will never fully belong. It also fails to acknowledge structural barriers such as racism, gendered disadvantage, and insecure legal status, which limit access to the very criteria by which belonging is judged.

At the same time, the White Paper includes proposals that warrant more careful consideration. These include the option for some UNHCR-recognised refugees to transfer into the Skilled Worker route, which may offer new pathways but raises important questions about the trade-off between labour migration status and refugee protection. There is also a more sympathetic provision for young people turning 18 who have been unable to regularise their status, suggesting a willingness to support this often-overlooked group. However, other elements—such as the proposed increase in salary thresholds and the suggestion of fast-tracked citizenship for those who can demonstrate economic or social ‘contribution’—raise concerns about the commodification of belonging (Anderson (2013). Linking citizenship to wealth creation risks reinforcing inequality and sending mixed messages about who is valued in UK society.

Conclusion: toward an evidence-based migration policy

The Restoring Control White Paper does not represent a break with the past but an intensification of exclusionary approaches that have long proven ineffective and harmful. While asserting the importance of “fairness” and “integration”, the proposals promote division, deepen precarity, and ignore readily available, evidence-based solutions to the challenges they claim to address. This White paper overlooks decades of research on the social, economic, and civic contributions migrants make to British life.

At IRIS we call on policymakers to resist framing migration as a problem to be managed through exclusion and control, and instead to develop policy that is grounded in the reality of migrant lives, empirical evidence about what works and the social / economic contributions of migrants. We call for an approach to immigration policy that is not only grounded in evidence, but also respects basic human rights, and reflects the diversity and complexity of contemporary migration. Such an approach would:

- Reform NRPF and family migration rules to reduce child poverty and enable integration

- Recognise care work—paid and unpaid—as a valid social contribution

- Restore the right to work for asylum seekers to promote self-sufficiency

- Reframe integration as a reciprocal process supported by inclusive services and infrastructure

Policymaking driven by short-term political calculus and ‘sending it away’ solutions (Hall et al..1978), rather than long-term social investment, ultimately weakens the fabric of our shared society. Migration is not a problem to be solved, but a reality to be understood and shaped through inclusive, principled governance. As a centre dedicated to rigorous, lived experience research on migration and superdiversity, IRiS stands ready to support policymakers in designing inclusive, equitable approaches that reflect both global realities and the needs of our diverse communities.

Further reading and research from IRIS

See Working Paper Series. IRIS, University of Birmingham. Available at: https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/superdiversity-institute/publications/working-paper-series

Acknowledgements

Thanks go to Dave Newall, Walsall Council for his comments on the draft of this response.

References

Anderson, B. (2013) Us and Them? The Dangerous Politics of Immigration Control. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Children’s Society (2020) A Lifeline for All: Children and Families with No Recourse to Public Funds. London: The Children’s Society. [Available at: https://www.childrenssociety.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-11/a-lifeline-for-all-report.pdf]

Commission on the Integration of Refugees (2024) From Arrival to Integration: Building Communities for Refugees and for Britain. Cambridge: Woolf Institute. Available at: https://refugeeintegrationuk.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/CIR_Report.pdf

Hall, S., Critcher, C., Jefferson, T., Clarke, J. and Roberts, B. (1978) Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State and Law and Order. London: Macmillan. Available at: https://sociologytwynham.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/policing-the-crisis.pdf

Home Office (2025) Restoring Control Over the Immigration System: White Paper. London: Home Office. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/restoring-control-over-the-immigration-system-white-paper

Inclusion London (2024) Briefing: Changes to disability-related social security and work. London: Inclusion London. Available at: https://www.inclusionlondon.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/MP-briefing-on-disability-benefits-cuts-and-work.pdf

Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) (2024) How have English councils’ funding and spending changed? 2010 to 2024. London: IFS. Available at: https://ifs.org.uk/publications/how-have-english-councils-funding-and-spending-changed-2010-2024

Jolly, A. and Gupta, A. (2024) ‘Children and families with no recourse to public funds: Learning from case reviews’, Children & Society, 38(1), pp. 16–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12646

Jolly, A., Singh, J. and Lobo, S., 2022. No recourse to public funds: a qualitative evidence synthesis. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care, 18(1), pp.107–123. [Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMHSC-11-2021-0107]

Lift the Ban Coalition (2021) Lift the Ban: Why giving people seeking asylum the right to work is common sense. London: Refugee Council (on behalf of Lift the Ban Coalition). Available at: https://cdn-e2wra3va3xhgzx.cityofsanctuary.org/uploads/sites/120/2020/07/Lift-The-Ban-Why-Giving-People-Seeking-Asylum-The-Right-To-Work-Is-Common-Sense.pdf

Migration Advisory Committee (2022) Adult social care and immigration: a report from the Migration Advisory Committee. London: The Stationery Office (Cm 665). Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/626931768fa8f57a40cf7e7b/E02726219_CP_665_Adult_Social_Care_Report_Elay.pdf

Phillimore, J. (2021) Refugee integration opportunity structures: Shifting the focus from refugees to context. Journal of Refugee Studies, 34(4), feaa012. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feaa012

Hourani, J., Block, K., Phillimore, J., Bradby, H., Ozcurumez, S., Goodson, L. & Vaughan, C. (2021) Structural and symbolic violence exacerbates the risks and consequences of sexual and gender‑based violence for forced migrant women. Frontiers in Human Dynamics, 3, Article 769611. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2021.769611

Refugee Action (2023) Hostile Accommodation: How the asylum system is cruel by design. London: Refugee Action. Available at: https://www.refugee-action.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Hostile-Accommodation-Refugee-Action-report.pdf

Skills for Care (2023) The state of the adult social care sector and workforce in England 2023. Leeds: Skills for Care. Available at: https://www.skillsforcare.org.uk/Adult-Social-Care-Workforce-Data/Workforce-intelligence/documents/State-of-the-adult-social-care-sector/The-State-of-the-Adult-Social-Care-Sector-and-Workforce-2023.pdf

The Guardian (2024a). Protesters shouted ‘get them out’ at Merseyside asylum seeker hotel, court told. The Guardian, 9 January. [Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2024/jan/09/protesters-shouted-get-them-out-at-merseyside-asylum-seeker-hotel-court-told

The Guardian (2024b) Urgent protections needed for asylum seekers in hotels, say refugee groups. The Guardian, 26 August. [Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/article/2024/aug/26/urgent-protections-needed-for-asylum-seekers-in-hotels-say-refugee-groups]

Leave a comment